Danielle Shlomit Sofer

Collaboratively edited with Clifton Boyd and Stephen Lett

Content Warning: The following post discusses rape and sexual assault in the academy.

All of the major scholarly music societies have subgroups devoted to queer themes these days.[1] As late as 2016, however, no independent body devoted to supporting queer music scholars’ inquiry into queer issues existed. After I met ethnomusicologist Thomas Hilder (Figure 1, bottom right) through Freya Cloud Jarman (not pictured, but always present), we together decided to organize such a group—what became the LGBTQ+ Music Study Group. Our first social gathering met in London six years ago, and in April 2022, just before writing this blogpost, I attended the most recent Symposium “Queer, Care, Futures,” in Vienna, Austria.

***

Upon a flat or smooth surface, queers in the academy appear as staggered, dislocated spaces between words arranged in a paragraph such as this one. Each space a perforation, indenting the smooth space, puncturing it, in one side and out the other. Perforations take on a depth imperceptible to those whose vantage merely skims the surface. Dedicated spaces afforded by these ever-so-slight indentations are necessary to foster the sense of belonging that anyone longs to feel in public. We occupy and protect these spaces for now, until a time when there is no difference between our sense of self during our day-to-day activities and our existence in such a humble queer bubble as the Study Group.

***

On my way back to Dayton, Ohio after the conference I was violently thrust back to this world’s surface. In the security line at Heathrow airport in London, I was physically assaulted by a security officer and subsequently escorted away to a more remote area. During those few moments, I experienced the familiar tug of the dreamworld in which I find myself when my complex Post Traumatic Stress (c-PTSD) response kicks in: reliving past sexual traumas from childhood abuse, multiple instances of rape (beginning at the age of 12), and an incident along these lines I experienced in my own on-campus office a few years back.[2] Before, I silently capitulated to the demands of another against my will.

But not this time. It should be considered unconscionable for an officer of the law to violently approach an unarmed citizen, just as speaking out against my abusers should have led to their persecution, not mine.

***

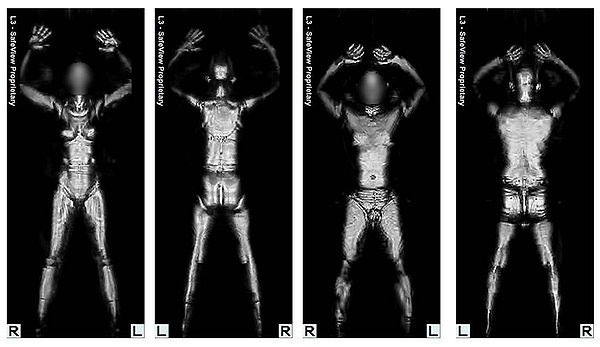

While writing my book Sex Sounds (forthcoming), I was thinking a lot about Lauren Berlant’s argument that our conceptions of privacy and property hinge upon “a boundary between proper and improper bodies” (1995, 380–81).[3] Entering the millimeter body scanner at the airport—the one that allows them to visibly undress you in public (Figure 2)—I was again thinking of Berlant’s words and of the list of sexualizing codewords TSA agents have for female passengers, there are nine according to one former agent.

***

At the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory (SMT) in 2019 many members were shocked by how the conference seemingly centralized the themes of “identity politics.” For others it was a welcome but long overdue spotlight. That year, the Society also solicited recommendations from members of the Queer Resource Group on forming a Standing Committee on LGBTQ+ Issues to represent its queer members and liaise with the Executive Board. But, by far, the most noted event that year—publicized more widely than any subject debated by our Society prior—Philip Ewell presented his research on music theory’s “white racial frame” at that conference’s Plenary Session, commencing the famous “Schenker was a racist” debacle. Surely we are all grateful that this dam has at last been rushed, its façade finally crumbled. And yet, I cannot help but notice that, not only were there other speakers on this panel—Yayoi Uno Everett, Joseph Straus, and Ellie M. Hisama—but that the heinous acts outlined in the last talk appear to have been completely forgotten:

A network of sexual violence and bullying festers in the underbelly of our discipline.

Hisama’s plenary lecture exhibited sound recordings from 1997 of the late Milton Babbitt. She kept the tapes hidden all this time for fear of what would happen to her if she exposed these unspoken beliefs to his disciples, many of whom now dominate the profession. On the recordings, Babbitt sexually objectifies his colleagues in detail and unabashedly announces his spite for the so-called “homosexual domination” over musical societies and awards committees. He claims this domination prevented him and his allies from gaining their desired recognition for their work (Hisama 2021, 345), the “proper” respect he believes they deserve.

She also presented testimonies from several women music theorists who have experienced targeted harassment, sexual harassment, and bullying at work. As the testimonials show, Babbitt’s homophobic and anti-woman sentiments still haunt the halls of our universities and the vacant hotel rooms of past conferences. In the wake of these revelations, the Society issued no statement on sexual violence nor harassment.[4] Nothing at all has been done. Sexual assault and rape are simply and quietly swept under the rug.[5]

Remarks like Babbitt’s are being repeated RIGHT NOW in 2022. Indeed, Babbitt’s comments echo in many I have heard on the job market and later as an assistant professor. Aside from the unfortunately typical microaggressions and misgenderings, professional spaces, because of their insularity, give the appearance of an echo chamber. According to Berlant: “Dead citizenship, which haunts the shadowland of national culture, takes place in a privacy zone” (1995, 382). The shared principles that bind past members are implicit, hidden to newcomers who are have yet to become citizens or naturalized as such, by which I mean accustomed, habituated and settled. When abiding by unspoken rules, it is easy to misstep, to lose one’s way, and because of this newcomers often feel uneasy—unsettled. We do not know who the aggressors are. And we have often already lost the victims and their guiding whispers, “rumors”—they’ve either abandoned the Society or the academy altogether. Entering our Society is like walking down a long winding corridor in the dark when you know there is a potential attack looming. It has neither preventative measures nor recourse. In this way, individual members of the Society become complicit by way of silence. Whether out of indifference or discomfort, the effect is the same: silence imposed as a benchmark of “professionalism,” which is really just another right to privacy bestowed upon those “proper,” acculturated bodies. And because they do not speak (those who came before us, who may have perpetrated, witnessed, or even experienced an incident), we, too, may see no chance to speak.

***

The SMT Policy for Harassment was last updated three years ago, following closely the wording of an American Musicological Society policy. Although the policy rightly identifies all members as equally accountable for reporting offending actions, there is no concrete guidance on how to handle such situations within SMT other than contacting the Society’s president or other members of its Executive Board. There is no obvious benefit to coming forward to report incidents, and all the risk is taken by the victims. This essay deliberately refrains from making suggestions to improve this policy, since any proposed actions should be in consultation with the Society’s membership.

Privacy in our Society, citizenship/membership in the Society, even life in the fullest sense in proximity to the Society, is extended only to certain members of our discipline, to those who are deemed entitled to those privileges—proper bodies. While we may have collectively (if tacitly) agreed that, hey, maybe Schenker was a racist after all, could it be that, as compromise for this little morsel of validation, our Society lets Babbitt’s comments about the “homosexual domination” slide? Quietly we swallow these beliefs, and mere beliefs become rule. If “homosexual domination” sounds old-fashioned to you, what about sexual assault or rape?

Danielle Shlomit Sofer is Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Music Technology at the University of Dayton.

Notes

I am tremendously grateful to the members of the Engaged Music Theory Working Group. Even as I transitioned out of and then back into academia, they always made me feel welcome. I had the immense pleasure of working with dedicated and dutiful editors Clifton Boyd and Stephen Lett who enthusiastically volunteered to usher this post to publication. Thank you also to the ever generous Reb Lentjes for her suggestions and time.

[1] This blog series is supported by a subvention grant from the Society for Music Theory (SMT). [return]

[2] It is well documented that individuals belonging to LGBTQIA+ communities experience incidences of sexual abuse and trauma at disproportionately high rates. Within this community, trans and non-binary individuals have “shockingly high levels of sexual abuse and assault” (Office for Victims of Crime 2014), with the highest rates among trans people of color. For statistics I collated specifically for SMT and an analysis of issues arising when seeking to calculate the percentage of members of SMT who identify with a category under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella, see Sofer 2019. [return]

[3] Berlant demonstrated, via a material history of Parental Advisory labels, how the elite classes (citizens) use the law to wage war against those whose rights to privacy (i.e., protection from public scrutiny—whether racial, sexual, musical, or otherwise) are not protected by law. I do not have space here to lay this out, but it is easy to imagine how hip-hop producers and musicians may experience negative outcomes in copyright cases, for example, if they are viewed by the court as lacking protection from the law on account of racial and musical identifiers (Rose 2008; Williams 2013). [return]

[4] I am told SMT is forming a committee concerned with hiring practices in the discipline. [return]

[5] A few months before this blogpost was published, two senior members of the Department of Music at Harvard University were named authors of a letter in support of retaining a male colleague who had several years’ worth of complaints lodged against him. This letter has since been retracted. [return]

Works Cited

Berlant, Lauren. 1995. “Live Sex Acts (Parental Advisory: Explicit Material).” Feminist Studies 21 (2): 379–404. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178273.

Hisama, Ellie M. 2021. “Getting to Count.” Music Theory Spectrum 43 (2): 349–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtaa033.

Office for Victims of Crime. 2014. “Sexual Assault in the Transgender Community: Chicken or Egg?” Responding to Transgender Victims of Sexual Assault, June. https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/pubs/forge/sexual_ch_e.html.

Rose, Tricia. 2008. The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk about When We Talk about Hip Hop—and Why It Matters. New York: Perseus Book Group.

Sofer, Danielle. 2019. “Queer Stats.” Presented at the Queer Resource Group Business Meeting, Society for Music Theory, December 9. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WtX1VbOsyFU.

———. (forthcoming). Sex Sounds: Vectors of Difference in Electronic Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Williams, Justin A. 2013. Rhymin’ and Stealin’: Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.