Miguel Garutti

Translated by Noel Torres Rivera.

Presione aquí para leer el texto en español.

Translator’s Note

Last summer, a few months after finishing my doctoral degree, I received the invitation to write a post for the recently launched Engaged Music Theory Working Group’s blog. Having been somewhat involved with this young collective since its pre-pandemic beginnings, I felt extremely honored that my fellow members had considered me, along with talented scholars Danielle Sofer and Vivian Luong, to contribute to this year’s series. Interestingly, the invitation came right at a time when I was invested in a summer reading group on postcolonial and decolonial studies led by Nalini Natarajan (UPR, Río Piedras). A group of mostly junior scholars, we read and discussed primary and secondary sources on the topic with a dual purpose: seeking to better understand current academic discussions within our field as well as devising ways in which each of us could reconsider our own academic and pedagogical work through those lenses. Furthermore, as a colonial subject, I used this opportunity to revisit the cultural, social, political, and economic forces that continue to impact the lives of many of us Puerto Ricans.

Certainly, the experience was eye-opening, yet also emotionally upsetting. As a nonwhite gay man from a Spanish-speaking region, with a working-class upbringing and an all-public education, I am easily lumped into the heterogeneous group of scholars that legitimately claim a status of marginality (or coloniality, so to speak) in North American academic, social, and political contexts. However, in spite of all hardship (of which I can speak plenty), when I consider my current position—a middle-class citizen of the so-called “First World,” working as a tenure-track professor in an academic community of uncontested supremacy—another way of understanding the complexity of my identities surfaces: one that places me on the privileged side of the seesaw in relation to most academics, some of them my own friends, who work outside the places on earth where academic capital has accumulated. This realization collided with my academic motivations. While I had begun asking myself, “How can my work be decolonial?,” I was now rephrasing: “Can my work ever be decolonial?” Furthermore, I reconsidered what I have always thought to be a major elephant in the academic rooms I frequent: How can we, particularly music academics working in North America, categorically ascribe moral value to our work when its main purpose often seems to be personal gain (getting a job, working towards tenure, acquiring institutional prestige, etc.)?—And when such work is often enabled by institutions that derive their capital (economic, cultural, and social) from a privileged position within an unredeemable, unfair, and unequal system? In other words, and talking specifically about the “north”/“south” divide at the center of my own work: Is the solution to coloniality really, then, for us—academics with greater access to resources—to insist upon speaking for the Other while deriving benefit from it? Aren’t scholars around the world already making those claims? Shouldn’t we just listen?

There is plenty to unpack here. However, a lengthy discussion is not the purpose of this introductory note. Still I repeat what is obvious to many: that when calling in our circles for much-needed academic reforms, through which we could firmly obliterate damaging and established power dynamics based on race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and ableism (among other categories), we also need to acknowledge and act against the imperialist and—why not?—colonialist forces that constantly condition the work of scholars outside and “below” North America. For this reason, and with no claim to originality, I have decided to cede the opportunity offered to me to share my own work and instead do what I was once told would be a “waste” of my own time, an “obstacle” to my own academic progress: translate, into English in this case, the contribution of a fellow scholar, the composer and producer Miguel Garutti (Universidad de Buenos Aires). For this reason too our editor, EMT member Nathan Pell, has chosen to remain off the masthead. Perhaps acts such as ours—ceding power or title in the name of a political goal—will strike the reader rather in the same way that, in the text below, Kusnir suggestively leaning forward his hooded head failed to impress the critic Müller: merely performative, bizarrely solemn, empty of significance. Perhaps that cynicism is warranted. Nevertheless, the text you are about to read, in its final version, was created through countless hours of scholarly care by a group of friends, and friends of friends, working collaboratively across two, sometimes three continents, and in the service of music made to “un-compose” barriers between sound and a turbulent world. Amidst the petty posturing of academic politics, is it possible that the sort of artistic-scholarly engagement proposed here “expresses,” as Garutti asks, “in our current world some sort of commitment to reality?”

—Noel Torres Rivera (University of Missouri-Kansas City)

***

Experimentaciones sensoriales comprometidas: comentarios sobre Experiencia poliartística de Francis Schwartz y Eduardo Kusnir

Note on the Title: Below we have rendered comprometidas (adjective modifying the title’s “Sense Experiments”) as “committed,” though on the Latin American left the word denotes a political attitude more revolutionary than its stiff English counterpart can commit to. Differences aside, these words customarily translate the French engagé, Sartre’s term for art that actively pursues social or political reform.

un concierto

“Those were sinister times.” That was the first thing Eduardo Kusnir told me. I was visiting Kusnir (b. 1939) because I wanted to know what he remembered from a concert he had done with fellow composer Francis Schwartz (b. 1940) at the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) in Buenos Aires on July 15, 1975. I had come across some old newspaper headlines announcing and reviewing the event several months earlier while doing dissertation research at the National Library:

“A poly-artistic show will be presented today, with an array of stimuli for different senses” (La Opinión, July 15, 1975).

“In a spectacle at CAYC showcasing their combined artistic research, two musicians manipulated modern forms of communication” (La Opinión, July 20, 1975).

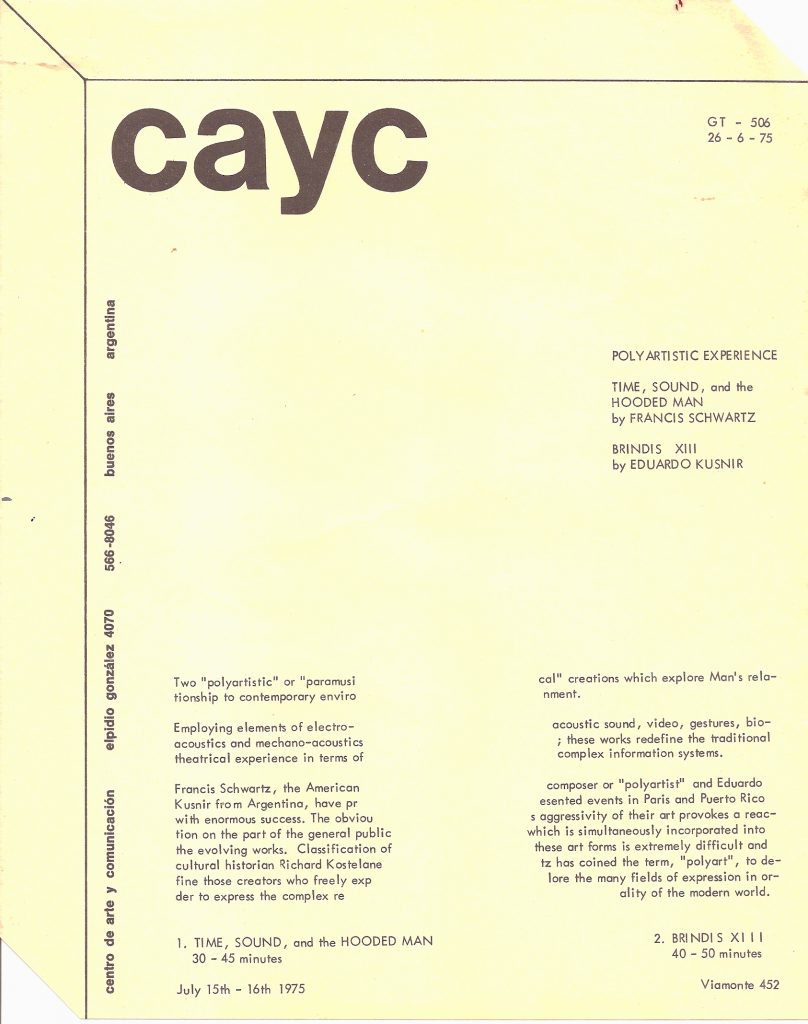

The show was titled Experiencia poliartística (“Polyartistic Experience”) and, according to what Schwartz described to the critic Martín Müller, it consisted of two works “merged into a fixed structure that allowed for some aleatoric moments.” The first one, Schwartz’s Tiempo, espacio y el hombre encapuchado (“Time, Sound, and the Hooded Man”), was meant to induce in a “predominantly young” audience a multi-sensorial experience through the use of video screens, audio tapes/reels, perfume, a synthesizer, and the actions of four performers. Off to the side was Schwartz himself—at an audio-video console watching the action and the screens. An “artist-researcher,” a potential “creator of the future,” in “semi-darkness,” manipulating “his strange technological alchemy.” On the screens, close-ups of a bearded face, fingers, and an arm stood out to Müller; of the sounds, “varied rhythmic schemes, an ample diversity of timbers, and juxtaposed sonorities.” “Indistinct flower aromas” occasionally filled the room. Standing opposite Schwartz, a man would tilt his bagged head forward. The sack removed—the young man onscreen was Kusnir.

It was right at that moment that the second work of the program, Brindis XIII, began. This work consisted of Kusnir reading a chapter of the thesis that he had presented a year earlier for his Ph.D. at Paris VIII. At his command, young girls performed slow and pleasing actions: stroking their own hair and caressing cigarettes. Unimpressed, Müller described Kusnir’s text as “surreal,” at times inaudible, languid, saturated with monotony.

Reading the review for this concert confirmed my suspicions from the headlines: Kusnir and Schwartz presented this as a concert of “artistic research”; in which sensorial experimentation, avant-garde music, and political symbology were blended together without distinction. This at a time when, above all, an artist was expected to make their political commitment explicit in their art—a commitment that in those “sinister times” tolerated ever fewer sensory experiments, formal vagaries, and ironic estrangements, like those put forward by this concert. Today, regardless of what the reception of Kusnir and Schwartz’s works would have been back then, could we consider and reconsider whether such a concert—one that embraced the ominous, stretched solemnity to the limits of absurd humor—expresses in our current world some sort of commitment to reality? A surreal one, perhaps?

***

arte comprometido

Until recently there was a general belief among cultural historians that, as far as Buenos Aires’ art world went, the concert music scene was one of the city’s less radical during the 1960s and 70s. The least committed of the vanguardistas, the most detached from the world’s noise. Within the visual arts, not only did many artists articulate their solidarity with revolutionary causes through their work; quite a few even renounced art for political action (Giunta 2001, Longoni 2014). Actors and playwrights discussed strategies for constructing a national theater tradition, popular and free from foreign (that is to say, in this context, imperialist) influences (Verzero 2013, Devrient et al. 1975). Filmmakers documented and denounced the injustice of the economic system in secret, avoiding censorship through clandestine screenings in neighborhoods, factories, and universities (Oubiña 2011). The new music scene, though allegedly less concerned with social issues, still shared the same spaces and audiences with those more radically committed revolutionary artists. Therefore, the disconnection or indifference could not have been absolute.

During the last few years there has been an increasing attempt to trace the particular ways in which politics did intervene in concert halls. I here provide a list, not exhaustive, of works and composers that advanced the incorporation, with more or less remove, of political commitment into their productions.

§ Dancer and choreographer Teresa Monsegur (b. 1942) and her partner, composer Gabriel Brnčić (b. 1942) left Argentina faced with threats by the infamous Alianza Anticomunista Argentina (“La Triple A”), which led to a simulated execution in the garden of their house. In both her native Chile and Argentina, Monsegur had worked to bring modern dance to jails and neighborhoods. Just a few months before exile, Monsegur premiered a modern dance work at the Teatro San Martín in Buenos Aires that portrayed “monsters who dominated the people and the people who ended up rebelling and overcoming the monsters,” according to Graciela Rusiñol, one of the dancers in the show.[1] This performance included an electroacoustic work by Colombian composer Jaqueline Nova (1935–1973), Creación de la tierra o canto de los indios tunebos (“The Creation of the World or the Song of the Tunebo Indians,” 1972).[2] This was four years after Brnčić’s orchestral work Volveremos a las montañas (“We will Return to the Mountains,” 1969)—its title refers to Che Guevara’s revolutionary army in Bolivia—had its premiere cancelled because of an alleged bomb threat at the Teatro Colón, Argentina’s most prestigious concert hall, where the premiere was taking place. Brnčić also demonstrated his political commitment in the “Introduction to Sound” course he used to offer at the Centro de Investigaciones en Comunicación Masiva Arte y Tecnología (CICMAT). In this course, Brnčić articulated the necessity of training professional technicians who could counteract “subtle forms of cultural penetration,” arguing for technical instruction with a “mind to include consideration of social benefit” (Brnčić 1973).

§ Eduardo Bértola (1939–1996) returned to Argentina in 1971 after some time at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) in Paris—the centers of high modernism continued to attract new generations of Latin American composers—to carry out his “social duty” in the “social revolution” and “cultural liberation” of Latin America. Interested in associating avant-garde music with the revolutionary cause, Bértola composed unprocessed radiophonic collages that, with esthetic distance mediating, traced the political signals underlying mass media’s apparently trivial content. He also composed the electroacoustic work Gomecito contra la Siemens o El diablo de San Agustín (“Gomecito v. Siemens, or The Devil of Saint Augustine,” 1973), in solidarity against a case of injustice committed by this international corporation (Paraskevaídis 2001).

§ A short distance away from Buenos Aires, in the Uruguayan capital Montevideo, Graciela Paraskevaídis (1940–2017) and Corihún Aharonián (1940–2017) developed a program of action—compositional and musicological—that advocated the construction of a Latin American esthetic, critical of the power of attraction held by certain metropolitan centers. Starting in 1971, they experimented with a new method of self-managed institutional organization through the Cursos Latinoamericanos de Música Contemporánea (CLAMC), gathering musicians and educators from across the continent a total of fifteen times between 1971 and 1989 (Paraskevaídis 2014).

§ Oscar Bazán (1936–2005), though a technician at the electronic music laboratory of CICMAT, proposed an alternative to the endless thirst, predominant at the time, for technological progress: austerity—works inspired by music from the region employing only the most elemental techniques offered by the ARP 2600 synthesizer (Garutti 2015, Perrone 2016, Domínguez Pesce 2021).

§ The Movimiento Música Más found another way of innovating, one in which we can read an esthetic sensibility close to political renewal. This group organized “free improvisation” inside and outside concert halls, from the Teatro Colón to a public bus on the 7 line (Raffo Dewar 2018).

§ The Grupo de Experimentación Musical at CICMAT, composed of professors Gerardo Gandini, José Maranzano, Francisco Kröpfl, and Brnčić, offered didactic lectures before its 1973 concerts. In these lectures they connected experimentation with the democratization of musical practice, replicating mid-1960s Italian discourses from groups such as Nuova Consonanza and Musica Elettronica Viva (Garutti 2018). Arguments grew ever less subtle as the series progressed, to such an extent that they even included quotes from Juan Perón in an attempt to placate the very audience members (some were far-right Peronists too) who found these avant-garde artistic expressions too abstract and, therefore, too far removed from the country’s political situation. Similar criticisms caught up to Movimiento Música Más, which as a result disbanded that same year. As Noberto Chavarri, one of its protagonists, later admitted, MMM was more interested in innovation than in revolution (Tapia 2016).

It is important to remember that not all art produced during the 1970s in Argentina was radical. The theaters on Avenida Corrientes (the “South American Broadway”), the greater part of commercial cinema and music heard on the radio, the galleries full of geometric abstraction, and other avant-gardes: all continued working with normalcy, more or less alien to politicization, more or less psychedelic, pop, modernist, or traditionalist. Kusnir and Schwartz’s work does not entirely adhere to either of these two positions. They were not indifferent to the political. For instance, in the notice publicizing Experiencia poliartística Schwartz expressed a desire for his spectacle to reach beyond “the minority’s leash,” outside of a “small circuit of sophisticated personages.” Nonetheless, the way he demonstrated his political interest—through the psychedelic, the ironic, the ambiguous, the technological—related more to those hardly committed mainstream poetics. How then should we describe this middle position?

***

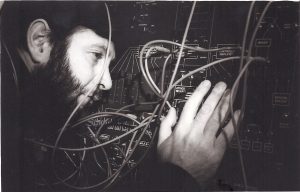

Kusnir caressing CICMAT’s ARP 2600, ca. 1975. Archivo de Música y Arte Sonoro Fernando von Reichenbach, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

lo surreal

The way the critic Müller characterized Kusnir and Schwartz’s concert, “surreal,” gave me an idea for rethinking how they differ from other composers of their generation. For I do see a similarity with some current trends in Buenos Aires today. A surrealist air indeed permeates the imagination of its artistic community. Every day we find in galleries and concert halls works committed to the unknown, the enigmatic, the mysterious, the miraculous, the fantastical, the dreaming, the daydreaming, the lyric, the precarious, the strange, the deformed, the animal, the intimate, the sinister. This is a surrealism different from the historic French kind, the avant-garde of the 1920s and 30s. It does not have a specific esthetic or political program; it is more ambiguous, more erratic. It escapes analysis. Its cause seems to be an attempt at dissolving the artistic law of non-contradiction, and its trick, by surfeit or by some defective act, ends up being discomfited surprise. Recuperating this brand of surrealism from negative critiques like Müller’s, artist and curator Santiago Villanueva proposes considering this particular affect of Buenos Aires’ art scene as surrealismo rosa (“pink surrealism”).

It is pink because it is the color used least by the avant-garde, a hardly serious color, more street-like and less pretentious. . . Pink surrealism is directly bound to the body, empathizes more with queer theory than with psychoanalysis, more with newspapers than with poetry. It is just that it is not presented as evident, it sneaks and cheats. (Villanueva 2021)

In Schwartz and Kusnir’s performance, the laboratory in which the “artist-operator” does his magic—the place of technological utopia—was shrouded in darkness. But whatever a hooded man says is incomprehensible; it is not articulated as an explicit critique of the technoscientific-imaginary, like that in Mauricio Kagel’s Anthithese (1962), where scientist reacts explosively towards machine. That night in 1975, in place of the real and the modern stood an artist-researcher reciting a languid daydream.

***

Concert program for Experiencia poliartística. Archivo de Música y Arte Sonoro Fernando von Reichenbach, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

espacios

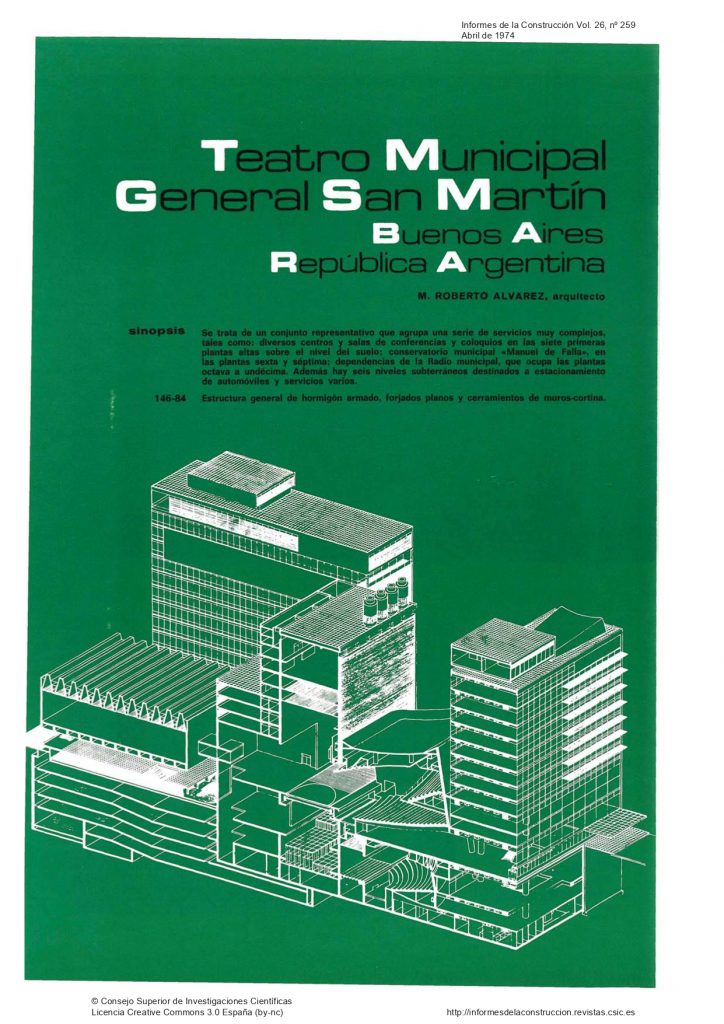

Throughout, I have mentioned two institutions a few times: CICMAT and CAyC. The creation of both institutions coincided with the demise of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (ITDT), a vital establishment for the neo-avant-garde movement in Argentina during the capitalist desarrollismo (developmentalism) of the 1960s (King 1985, Giunta 2001, García 2021). CICMAT and CAyC continued fostering the idea of the artist-researcher that the ITDT had promoted at its Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM). In contrast to CAyC and the ITDT, however, CICMAT was financed by the Municipality of Buenos Aires. It had originally proposed that the research it developed through its departments of Mass Communication, Technology, Topology and Dynamism of Visual Forms, and Contemporary Music would serve the community. The programming at CICMAT included pedagogical initiatives, public events, performances, and outreach in all its areas of specialization. CAyC, by contrast, was a private institution created by a group of artists and architects who favored the idea of arte de sistemas (a CAyC-specific term coined by its founder Jorge Glusberg, theorizing art as experimental-political research agenda) and continued with the internationalizing project that the ITDT had begun (Sarti 2013). CAyC operated from a commercial building by Viamonte, the street where Buenos Aires’ bohemian-intellectual elite had gathered since the late 1950s (Sebreli 1964). CICMAT operated from a building near the iconic Avenida Corrientes that—along with conference rooms, concert halls, and offices—also hosted the Municipal Radio, the Conservatory, and one of the city’s most important theaters, the Teatro General San Martín. This complex was an epicenter in the conflicts between the left and the Peronist right starting in 1973 and became a symbol of the new order that the military junta imposed in 1976. During the early 1970s hostility towards artist-researchers increased, as much for their apparently insufficient commitment to revolutionary causes as for their transgressions of artistic traditions. This situation in turn pushed artist-researchers further from audiences, since those musicians who decided to remain in their positions in order to protect their laboratories progressively cut down on public engagements (Garutti 2015). What spaces are left for musical research and experimentation in these increasingly sinister times?

Teatro Municipal y Centro Cultural General San Martín. Informes de la construcción, Vol. 26, No. 259, April 1974.

***

Kusnir y Schwartz

In 1969, some years after moving to Puerto Rico, Francis Schwartz had provoked scandal with the San Juan premiere of his work Auschwitz (1968). In a colonial house he recited a text he had written, as choreographer Carmen Biscochea danced to electronic sounds among barbed wire. Halfway through the work, Schwartz started to burn hair on stage while his students locked the hall’s exits from the outside. The audience, which included some American diplomats, rioted trying to escape the hall. When they finally did, the student-captors transformed into journalists and questioned attendees about their experience (Kusnir 1988). On the same trip to Buenos Aires that produced Experiencia poliartística, and just before presenting a concert at the Teatro San Martín, Schwartz was warned by CICMAT artist-researchers not to be too politically explicit in a situation that was already delicate and uncomfortable for them. Still, Schwartz performed a work for piano and tape: the tape produced electronic sounds and listed the names of Latin American cities where massacres had occurred. Schwartz told me that he had no problems with the censors. Kusnir suspects, in hindsight, that this work was not explicit enough: its abstraction did not make them uncomfortable. The piano’s dissonances masked the uncomfortable text, the concert hall neutralized the political provocation.[3] At least on that day.

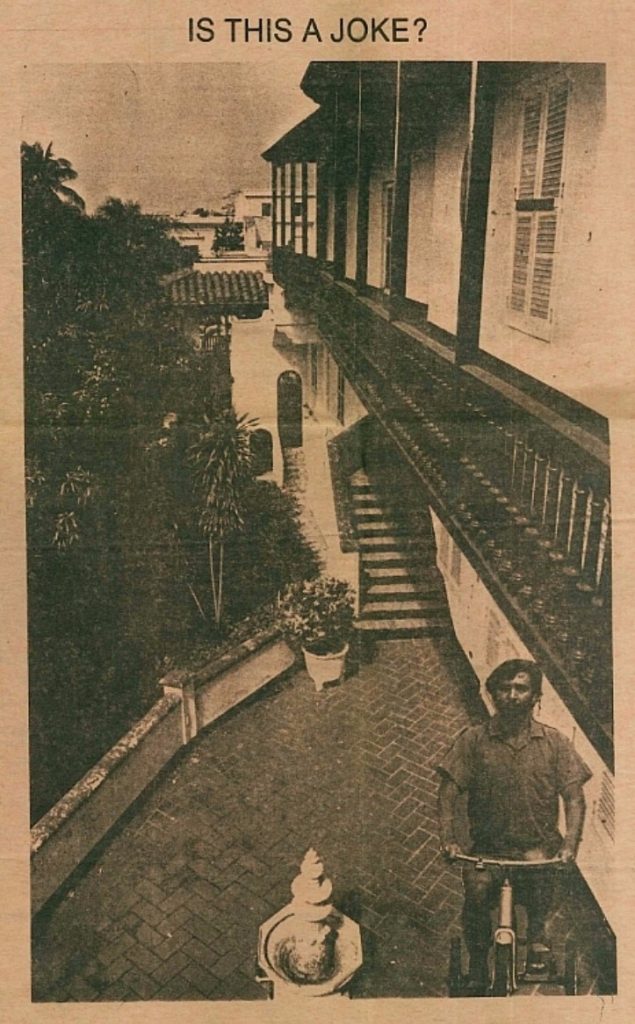

Kusnir on a tricycle in Old San Juan. “What Does a Tricycle Have To Do With Music?,” review of the premiere of Eduardo Kusnir’s Brindis No. 3 in San Juan, Puerto Rico, by Francis Schwartz. San Juan Star, October 7, 1973. Photo by Eddie Crespo. Archivo de Música y Arte Sonoro Fernando von Reichenbach, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

Eduardo Kusnir had returned to Buenos Aires in 1974, another stop during his nomadic years. Those began at the Bulgarian State Conservatory in post-Stalinist Sofia, followed by tours around the Red world conducting the Ballet Nacional de Cuba during the first years of the Revolution, a scholarship at CLAEM at the ITDT, another scholarship in Ghent, Belgium where he composed a chance-based radiophonic work, and yet another at Paris VIII to work on his doctoral thesis under the mentorship of Daniel Charles: Brindis. Una mirada a los juegos desgarradores del arte (“Brindis: A Look at Art’s Heartbreaking Games”)—or, in its original version, Brindis. la musique est-elle un langage universel? (“Brindis: Is Music a Universal Language?”). Kusnir’s thesis moves between reality and fiction in a set of what he calls brindis (“toasts,” like those given with wine), experimental instrumental theater works that he had presented at concerts and festivals since the late 1960s. The chapters of the thesis provide explanations for each of the works, including information about the compositional process. In order to differentiate those chapters from the actual Brindis, Kurnir titled them máquinas (“machines”), probably influenced by the machines désirantes (“desiring machines”) that Deleuze was proposing around the same time at the same university (Deleuze and Guattari 1972). In his máquinas, Kusnir came up with fictional characters that supposedly commissioned the works and detailed the hypothesis and inevitable fiasco of each investigation (that is, of each Brindis)—mocking the ironic falsehoods of the technocratic language that artist-researchers adopted. Apparatuses, modalities, and operation fields (like minefields, like encampments in the “unforeseeable”), org. charts, algorithms, regulated mechanisms, mental microphones that detect the intermittent pulsations of memorized music, catalogs of canonic composers’ signatures, inventories of pianistic gestures, teleguided and timed works, flowcharts, organizations, projects, structural integrities, perturbations in the system. Kusnir’s Brindis develops in a constant tension between composition-as-an-attempt-for-control and the uncertainty of a spectacle where anything can fail. Its back and forth between contradictory instructions—orders and counterorders, mends and tears, reality and fiction, irony and sincerity, production and reception—points to an attempt to dissolve one of the binaries that seems to bother him most: music and the world. Kusnir proposes the term “un-composition.”

To compose is to configure a series of original connections, without, in principle, any element being set aside or into a hierarchy. Nothing exists outside of music. We shall move towards un-composition, which will consist of mixing those elements in a common container that we call the concert-event, or rather, “the staged concert”: the music, the musicians, the orchestra conductor, silence, curtseys, tics, ovations, whispers, coughs, little biscuits, bracelets, the noisy zips of bags and purses, the instruments of the orchestra, the smoke from cigars and the cigars themselves, and—why not?—butterflies and spiders. (Kusnir 2005 [1974])

At the CAyC concert Kusnir read from this dissertation. Brindis XIII is a monologue, originally addressed to the dissertation committee, that describes “pleasant” actions—from smoking to listening to music on the radio—that performers should carry out on stage as they hear them. Through the instructions, Kusnir develops an alienated speculation. Taking advantage, for instance, of the word acción’s double meaning (as “action”; as “share” of invested capital), he proposed founding a bank: “an entity that could hold common funds containing all possible habits and slips, from which any interested individual would be able to deposit or, as it suited them, withdraw (by buying or borrowing) whatever actions they needed.” Transactions would be regulated by a Stock Exchange. Among ironies aimed for John Cage and the international financial system, far from articulating the expected conclusions of a doctoral thesis, Brindis XIII posits new enigmas—enigmas Kusnir insists upon, for the surrealist air that the critic Müller finds in this monologue is to be found in many of his other works.[4]

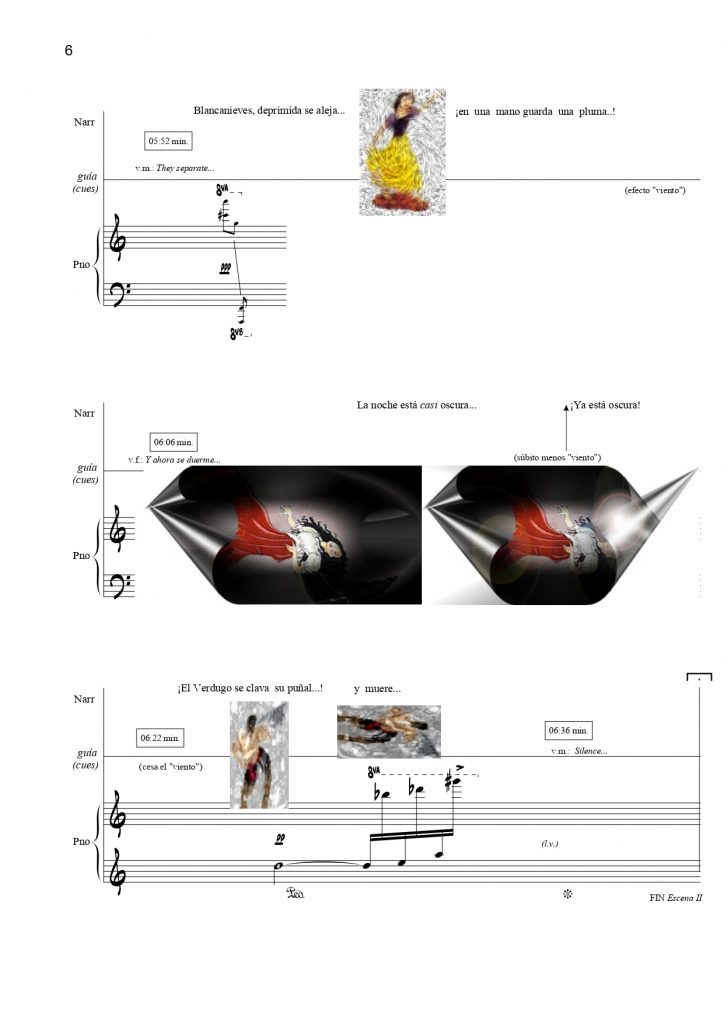

Pages 5 and 6 of Blancanieves by Eduardo Kusnir (2001). Archivo de Música y Arte Sonoro Fernando von Reichenbach, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

How should we interpret, politically, works that allude to politics but lack the disengagement of abstraction, exclude direct political references? Is it about a kind of political commitment that functions through irony without renouncing an honest and explicit presentation of the composer’s impressions and experiences? In Kusnir and Schwartz’s music, certainties are canceled. Their ironies impose a kind of distancing, necessary if you don’t want to get petrified staring horror right in the face. Impishness lightens the seriousness of customs and conventions, but triggers nervous smiles too. For the distance can never be cold enough. In their commitment to merge the marvelous with the abstract, they summon into the concert hall some of reality’s monsters.

Notes

[1] Conversation with the author, 2020. [return]

[2] [Editor’s note] “Tunebo” is the colonial name for the U’wa people, whose land covers the forests of Colombia’s Cordillera Oriental. [return]

[3] Conversation with the author, 2022. [return]

[4] Analyzing Kusnir’s sense of the surrounding political violence, Esteban Buch reads in some of his late 70s works, like Brindis X, an anticipation of “State terrorism’s sensory machine” (Buch 2016). The contact points between this work and Schwartz’s hooded man are evident: the pianist, blindfolded, gains knowledge of the score from two informants who dictate it to him. [return]

Works Cited

Brnčić, Gabriel. Course syllabus for “Introducción al sonido,” 1973. Fondo del Laboratorio de Investigación y Producción Musical, Centro Cultural Recoleta, Buenos Aires.

Buch, Esteban. Música, dictadura, resistencia. La orquesta de París en Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2016.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. L’Anti-Oedipe: Capitalisme et schizophrénie. Paris: Minuit, 1972.

Devrient, Eduardo, Irma Barrese, Oscar Rovito, Fernando Sendra, and Adolfo Berasategui. Cuaderno CICMAT 6: Primer encuentro de autores del teatro nacional. Buenos Aires: Área de Comunicación Artística del CICMAT, 1975.

Domínguez Pesce, Agustín. Escuchando archivos musicales: esto no es una historia del Centro de Música Experimental (UNC). Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, 2021.

García, Fernando. El Di Tella. Historia íntima de un fenómeno cultural. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2021.

Garutti, Miguel. “Modos de actuar en estado de excepción: la música electroacústica en los últimos años del CICMAT (1975–1977).” Afuera 15 (September 2015). http://revistaafuera15.blogspot.com/p/indice.html.

–––. “Música y escena en el CICMAT: ejercicios de improvisación y música electrónica entre las Audiciones Didácticas y el Plan de Reencuentro del Teatro con el Pueblo (1973–1976).” Unpublished conference presentation at TIMEAL 2018: “Teatro Instrumental. Música y escena en América latina (1954–2006),” Buenos Aires, December 5, 2018.

Giunta, Andrea. Vanguardia, internacionalismo y política: Arte argentino en los años sesenta. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2001.

King, John. El Di Tella y el desarrollo cultural argentino en la década del sesenta. Translated by Carlos Gardini. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Gaglianone, 1985.

Kusnir, Eduardo. Brindis : la musique est-elle un langage universel? Ph.D. diss., Université Paris 8, 1974. Revised and translated by the author as Brindis. Una mirada a los juegos desgarradores del arte. Posted 2005. http://eduardokusnir.com.ar/tesis.

–––. “¿Knock out musical? (II).” El Nacional (Caracas), January 8, 1988.

Longoni, Ana. Vanguardia y Revolución. Arte e izquierdas en la Argentina de los sesenta-setenta. Buenos Aires: Ariel, 2014.

Oubiña, David. El silencio y sus bordes: modos de lo extremo en la literatura y el cine. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2011.

Paraskevaídis, Graciela. “Eduardo Bértola.” Revista del Instituto Superior de Música 8 (2001): 12–59. https://doi.org/10.14409/ism.v1i8.

–––. “Cursos Latinoamericanos de Música Contemporánea. Documentación, I.” Posted 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20160411075504/https://www.latinoamerica-musica.net/historia/pdfs/prologo.pdf.

Perrone, Marcela. “La obra Parca de Oscar Bazán y la estética austera.” In Actas del Cuarto Congreso Internacional “Artes en Cruce”: Constelaciones de sentido. Buenos Aires: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2016.

Raffo Dewar, Andrew. “Performance, Resistance, and the Sounding of Public Space: Movimiento Música Más in Buenos Aires, 1969–1973.” In Experimentalisms in Practice: Music Perspectives from Latin America, edited by Ana R. Alonso-Minutti, Eduardo Herrera, and Alejandro L. Madrid, 279–304. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Sarti, Graciela. “Grupo CAyC. Historia.” Centro Virtual de Arte Argentino. Posted March 2013. http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/cayc/04_histo_01.php.

Sebreli, Juan José. Buenos Aires, vida cotidiana y alineación. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Siglo Veinte, 1964.

Tapia, Víctor. “Bondis, plazas y experimentación: Movimiento Música Más, los olvidados vanguardistas de la música argentina.” Universo Epígrafe, September 2016. https://universoepigrafe.wordpress.com/2016/09/18/bondis-plazas-y-experimentacion-movimiento-musica-mas-los-olvidados-vanguardistas-de-la-musica-argentina/.

Verzero, Lorena. Teatro militante. Radicalización artística y política en los años 70. Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2013.

Villanueva, Santiago. El surrealismo rosa hoy. Ensayo visual y crítico. Rosario: Iván Rosado, 2021.